Akseli Gallén-Kallela

THE ARTIST

b. 1865 — d. 1931

Espoo, Finland

Akseli Gallén-Kallela, as he would become, was born Axel Gallén on April 26 1865 into a Swedish-speaking family in Pori, on the west coast of Finland. Axel’s father, Peter Gallén was a widower — his first wife died in 1855 — and she was survived by five children. After her death Peter began working for the Bank of Finland in Pori, which is where he met the daughter of a local sea captain, Mathilda Wahlroos; they married in 1858 and Axel was their third child. Though their family was already large by today’s standards, it would grow larger still, as soon Axel had four more brothers and sisters, eventually totalling twelve Gallén children in all.

Peter Gallén left his bank position soon after Axel was born and went into private practice as a lawyer. It seems he wished his sons to follow him on the academic path as he sent Axel and his two older brothers Uno and Walter to the Ruotsinkielinen normaalilyseo grammar school in Helsinki. For Axel, traditional schooling wasn’t a good fit as he only completed three classes and in the mean time began attending evening drawing sessions at the Finnish Art Society and the Central School for Applied Arts. Following the death of his father in 1879, the 16-year-old Axel broke off his regular studies entirely and joined the Art Society as a full-time student in 1881.

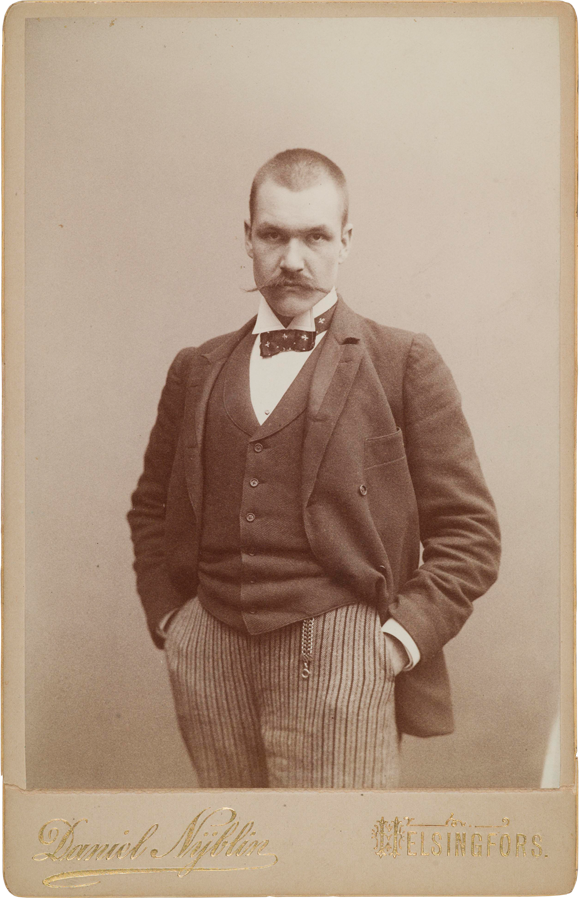

Encouraged by his mother and with help from a government grant, Axel went to Paris in 1884 and began studying at the Académie Julian. He subsequently completed some of his most famous early paintings, including Poika ja varis (Boy with a Crow, 1884) and Akka ja kissa, (Old Woman and Cat, 1885). He started splitting his time between Finland and Paris, attending the Académie Julian and other institutions where he practiced and perfected his art.

Gallén had long been preoccupied by the Kalevala, a collection of Finnish folklore poetry, that over time had been compiled into an epic 50 ‘song’ poem, similar to Beowulf or the Iliad. In 1889 he completed the triptych Aino, the first of many pieces to be inspired by the imagery of the Kalevala. It illustrates how Aino, the beautiful sister to Joukahainen would rather drown herself in a river rather than marry the Kalevala’s main protagonist, Väinämöinen. By way of explanation: Joukahainen and Väinämöinen were fierce rivals and Aino’s hand in marriage was the prize on offer if the latter could beat the former in a singing contest, which he subsequently did. In the story Väinämöinen is very old (maybe even as old as time itself as he’s sometimes featured in the Finnish creation myth, depending on the version being told) and is always depicted with a long white beard. Aino would rather kill herself than marry someone so ancient, which seems a little extreme, but nevertheless she proceeds to drown herself in a nearby lake. It’s not the last we hear of her however, as she is later reincarnated as a salmon and taunts Väinämöinen before swimming away forever.

"Little Finland must now set about creating a new Renaissance, i.e. new energy and life and a new world. It is needed now, in this situation and era of misery, weakness and melancholy decadence.”

Karalianism became a way of expressing true Finnishness, encompassing folklore, art, literature, poetry, design and architecture. It became the nation’s contribution to the art movement called Romantic Nationalism, which sought to define and protect— in this instance — Finnish heritage. It became particularly significant following Finland’s independence from Russia in 1917 and today the Kalevala and Gallén’s depictions of it have become cornerstones of Finnish history and culture. Aside from his artistic output, Gallén also personally aligned himself more closely with his native land, adopting the artists name Gallén-Kallela and using the Finnish version of his first name Akseli.

Gallén-Kallela was not just a painter — extensive travels around Europe and further afield to the United States and Africa influenced his work not only in style and subject matter but in technique too. Trips to Berlin and London in 1895 for example introduced him to new mediums like book plate illustration, wood cut printing and the Art Nouveau movement, which subsequently added a graphic quality to his work. Today Gallén-Kallela is admired as much for his versatility as he is a celebrant of Finnish culture. You can count paintings, frescos, stained glass, graphic woodcuts, illustrations, furniture design, architecture, award-winning contributions to the Finnish Pavilion at the 1900 Paris World Fair, and even designs for flags, official decorations and uniforms for a post-Russian Finland amongst his archive. It was this more design-centric, nationalistic work that saw him awarded an honorary professorship in 1919 and the University of Helsinki made him an honorary doctor in 1923.

Working until the end, in 1931 Gallén-Kallela was returning to Finland from a lecturing trip in Copenhagen when he contracted pneumonia and died on the 7 March. He was 65. Whilst it’s true that he left behind thousands of artworks, perhaps the most significant aspect of his legacy is how he helped shape the Finnish national identity. Very little of the artist’s work exists outside of Finland but you can see Lake Keitele, a beautiful depiction of the painting’s namesake in the National Gallery in London.

INFORMATION SOURCES

& FURTHER READING

– National Biography of Finland, Akseli Gallén-Kallela

– Wikiart, Akseli Gallén-Kallela

– The National Gallery, Lake Keitele

– Both English & Finnish (via Google Translate) Wikipedia pages on Gallén-Kallela’s life; plus, pages on:

– The Kalevala

– Romantic Nationalism

IMAGE SOURCES

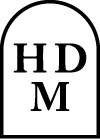

– Image 1 Studio portrait of Axel Gallén, circa 1890. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Common

– Image 2 Poika ja varis (Boy with Crow), 1884. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikiart

– Image 3 Akka ja kissa (Old Woman and Cat), 1885. Turku Art Museum, Turku, via Wikiart

– Image 4 Group portrait of Gallén and other students at the Académie Julian in Paris, circa 1880s. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 5 Muikunpaistaja (Woman Grilling Fish), 1886. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikicommons

– Image 6 Kauppatori, Pori; Toripäivä (Markets Square, Pori; Market day), 1880–1920. Satakunta Museum, via the Finna Archive

– Image 7 Cottage; interior, c. 1900. Lahti City Museum, via the Finna Archive

– Image 8 Aino, 1889. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikiart

– Image 9 Painting the central panel of the Aino triptych, circa 1890. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

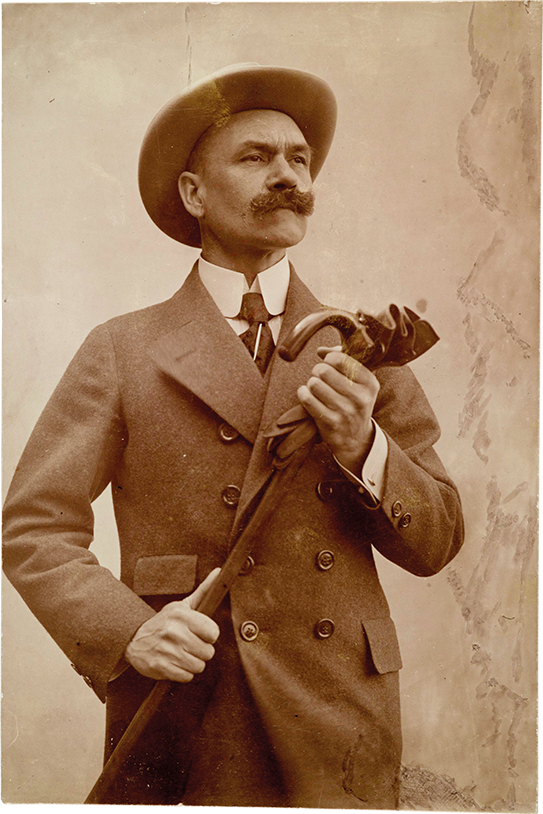

– Image 10 Portrait of Akseli Gallén-Kallela with a walking stick and gloves, c. 1915. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 11 Jumping with a pogo stick in front of the Gallén-Kallela home in Porvoo, 1923. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 12 Lake Keitele, 1905. National Gallery, London, UK, via Wikiart

– Image 2 Poika ja varis (Boy with Crow), 1884. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikiart

– Image 3 Akka ja kissa (Old Woman and Cat), 1885. Turku Art Museum, Turku, via Wikiart

– Image 4 Group portrait of Gallén and other students at the Académie Julian in Paris, circa 1880s. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 5 Muikunpaistaja (Woman Grilling Fish), 1886. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikicommons

– Image 6 Kauppatori, Pori; Toripäivä (Markets Square, Pori; Market day), 1880–1920. Satakunta Museum, via the Finna Archive

– Image 7 Cottage; interior, c. 1900. Lahti City Museum, via the Finna Archive

– Image 8 Aino, 1889. Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, via Wikiart

– Image 9 Painting the central panel of the Aino triptych, circa 1890. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 10 Portrait of Akseli Gallén-Kallela with a walking stick and gloves, c. 1915. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 11 Jumping with a pogo stick in front of the Gallén-Kallela home in Porvoo, 1923. Gallén-Kallelan Museo, via Flickr Commons

– Image 12 Lake Keitele, 1905. National Gallery, London, UK, via Wikiart